The old curmudgeon hands me a comb. What follows turns my whole life upside down.

It sits on a shelf in the farright corner of the little hardware shop on a rainy Birmingham high street, as if its waiting just for me. A sliver of light from the fluorescent tube catches it, and it flashes with a cold, silvery glow. I freeze, rooted to the spot. Its only a comb, but one Ive never seen before. The handle is smooth, faceted metal, mattefinished, and the teeth are not ordinary teeth at all. They shimmer with every colour of the rainbow, as if carved from ice that the sun is playing through.

I reach out, but my fingers stop a centimetre away. Inside me something snaps shut with contradiction. Why? a harsh inner voice asks. You already have a perfectly fine, practical comb at home. Its a waste of pounds. Foolishness.

I sigh and pull my hand back, yet I cant tear my eyes away. It looks alive, hypnotic. I picture it sliding through my untamed ginger locks and a smile tugs at my mouth.

Miss! Lovely comb, take it! the shop assistant exclaims, her grin wide.

Its all sold out, honestly. Only two left. Not only is it beautiful, its also incredibly practicalno snarls at all, she assures me.

I was just looking, I mumble, stepping back. I have my own, its fine.

I turn away from the shelf and head for the exit. A small mirror hangs by the doorway. I glance at my reflectionstubborn ginger tufts sprout from beneath my hat. The silly urge flares again.

No, I tell myself firmly. I must be frugal. Learn to say no to needless things.

I step onto the stoop, face turned into the cold February wind. The air snaps me out of the reverie. Down the slick cobblestones a familiar silhouette shuffles toward me: Pip Grimsby.

His real name is Paul Timms, but everyone in the neighbourhood knows him only by the grim nickname. An elderly man whose icy aloofness makes children steer clear. He never starts a conversation, and if you meet his gaze, its a heavy, scorching stare that makes passersby look away quickly.

Today hes in his usual garb: a worn rabbitfur coat, an old halffurred jacket, shabbily patched boots. The only thing that doesnt fit his dour image is the satchel slung across his shoulder. It isnt a battered rucksack or a cheap tote; its an elegant grey fabric bag, its flap embroidered with an exotic pearllike flower, clearly stitched with love and skill.

I stare at that otherworldly beauty, unable to look away. Our eyes meet. In his faded blue eyes a spark of ancient irritation flickers. I glance toward the display case, pretending to examine something, while my heart thuds in my throat.

A hoarse, cracked voice comes from right behind me. Hey! You up there!

I pretend not to hear.

Hey! Im talking to you! the voice grows louder.

I turn slowly. Pip Grimsby, creaking, climbs the steps of the stoop, his gaze fixed on me.

You live in this block, dont you? he asks, pushing his shaggy, grey eyebrows up with a finger. The scent of mint and old cloth clings to him.

I feel my cheeks flush. I um, yeah, I stammer, feeling foolish.

Um, yeahdoes that mean yes or no? he presses, and familiar angry glints dance in his eyes.

I simply nod, bracing for a clash.

He draws a heavy breath, and suddenly his look softens. Anger drains away, replaced by a strange, exhausted weariness.

Help me pick a present then, will you? Youre a girl, and Molly is my girl. My granddaughter lives far away. I havent seen her in years. Thats my Molly, he mutters, voice low, almost a whisper.

A flash of desperation, not malice, passes through his eyes.

Perhaps you should ask Molly what she wants? Even over the phone? I suggest cautiously. I just dont know what shed like

I cant ask, he snaps, his face hardening again. Its just how it is. Will you help? Choose something?

Thats when the idea hits me again: the same surreal comb, as striking as that bag. It would be perfect.

Fear still gnaws, but something inside trembles. I even dare to touch the sleeve of his coat.

Lets go, I say quietly. I saw something. I think its what she needs.

I lead him back into the shop, feeling the coarse fabric of his halffur coat under my fingers. He walks silently, leaning on a cane I hadnt noticed before. We stand again at the same counter.

Here, I point at the glittering item. I think this could please a young lady.

Paul Timms reaches out slowly, as if with effort, and lifts the comb. He turns it over in his large, deeply wrinkled, agespotted hands. He isnt looking at the comb but through it, as if seeing a distant memory. In that moment he isnt the Grimsby any more; he is simply a tired, lonely old man.

There are only two left, the shop assistants voice echoes again. Good combs sell out fast.

He fixes his gaze on me, and something stirs in his blue eyes. The corners of his mouth twitch, hinting at a smile, and he resembles an old, weary sailor who has just remembered a hidden treasure.

Ill take both, please, he says suddenly firm, and reaches into the inner pocket of his coat, pulling out a battered leather wallet.

I start to protest its too much, but the words choke in my throat. He counts the notes meticulously, the way a man who knows the value of every penny does.

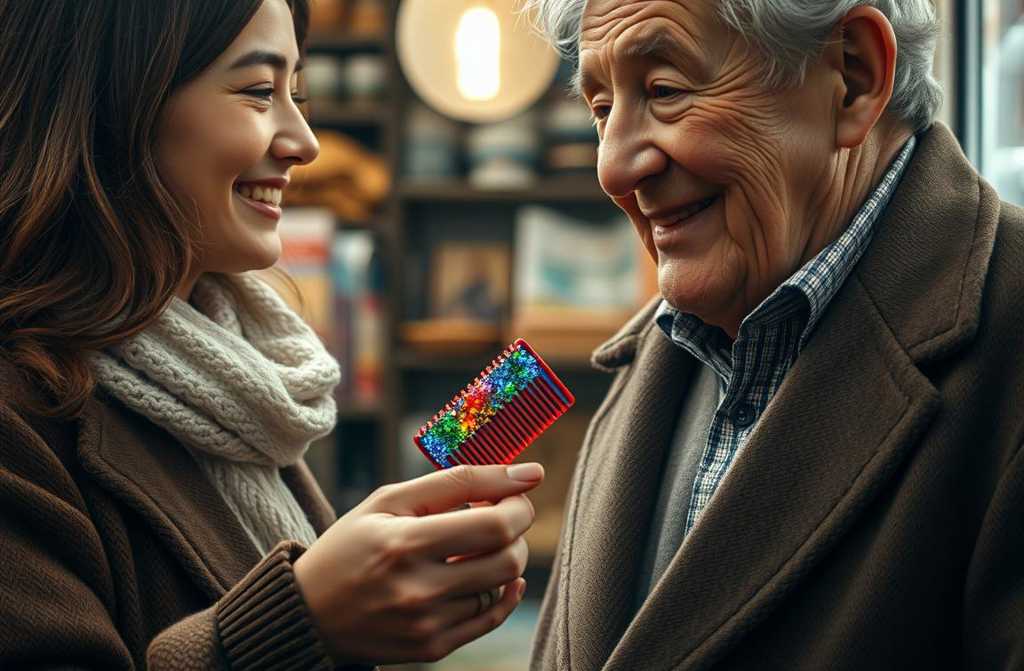

The shop assistant wraps the combs in two small paper bags. Paul Timms carefully places one bag into his exotic flowerembroidered satchel, cradling it as if it were fragile and priceless. He opens the second bag, lifts out the comb and hands it to me.

Here, take it.

I recoil as if hed offered a hot coal.

What? No, you its for your granddaughter I could get one myself

Take it, he insists, his hand steady, his tone now almost stern. Its a little giftfrom me, for you and for my Molly. Ill try to send her a parcel; maybe shell accept it And you you helped me today. Thank you.

The hopelessness in his voice when he talks about his granddaughter resurfaces. I stand mute, speechless, and take the comb. The plastic feels surprisingly warm, almost alive.

We leave the shop and walk in silence toward our building. I clutch the bag tightly, as if fearing it might disappear. In my head a question loops: Why? Why did he do that? No answer comes.

The quiet between us starts tense, then gradually eases. His breathing is heavy as we climb the slope, the only sound breaking the streets hush. I steal a glance at his shoulders; usually stiff, now they slump under an invisible weight.

Thank you, I finally manage, unable to stay silent. Its beautiful. Ill use it.

He simply nods, not looking at me.

Molly will be pleased, I suppose, I add cautiously.

He slows, sighs heavily, a sound that seems to rise from the depths of his old boots.

I dont know if shell be happy, he croaks. I dont know if shell even get it. My daughter Jan she wont give it to her. She doesnt want anything from me.

He falls silent, and we walk a few more steps in a heavy hush.

He blames me, he bursts out, as if a dam has broken. He blames me for not protecting his mother little Olly

His voice cracks and he coughs, pretending to choke.

She died in my arms. They said it was appendicitis, then peritonitis. The young doctor made a mistake Two precious days lost. She needed urgent surgery, but he gave her pills for a stomach ache. I trusted that doctor If only Id taken her to the hospital myself!

He wipes his face with his sleeve, and I pretend not to notice his trembling fingers.

My daughter came back only after everything happened. Its been five years. We never spoke. My granddaughter tried to call, but Jan forbade it. She loved her mother. And I I loved them. My life ended that day.

We reach our block. He stops at the entrance and turns to me. His face is twisted with a mute agony that makes my stomach knot.

Little Milly, dont turn away, come in. Ill show you what Olly made. Everythings still there. Shall we go? he asks, his eyes filled with hope and a plea for human kindness I cant refuse.

I nod silently. Fear drains away, replaced by a bitter understanding of his grief. I follow him up the stairs, the silver comb still warm in my pocket, feeling anothers huge sorrow become partly my own.

He unlocks the heavy iron door, and a strange, still air greets me. It isnt stale; it smells of stopped time, dry herbs, old paper and a faint trace of perfume that has almost faded away.

I step inside and freeze. The flat is not just tidy; its frozen like a photograph. Floors shine, every surface holds immaculate lacetrimmed napkins. On the wall hangs an old gramophone with a massive horn, beside it a neat stack of records. The windowsills are crowded with flourishing geraniums, their leaves glistening as if just polished.

But the most striking thing is a pink floral nightgown draped over the back of a chair, as if the owner just stepped out to change. On the vanity sits a small pile of rings, a strand of short pearls, an open powder box and a dried mascara tube.

It feels less like a home than a museum, a shrine where time stopped five years ago.

Paul Timms removes his halffur coat and carefully hangs it next to the pink gown. He moves toward the kitchen, his motions slower, almost ritualistic.

Sit down, Milly, Ill put the kettle on. Olly liked tea with jam. We have our own cherry jam, his voice echoes softly from the kitchen, hushed like a library.

I sit on the edge of a chair, afraid to disturb the fragile harmony. My eyes fall on a small table by the window. A stack of envelopes, tied with twine, sits there. I lean in; each envelope bears his sturdy, aged handwriting: To Jan, my dear daughter. Each bears a stamp reading Return to sender addressee deceased.

They havent even been opened. The cruelty of that silent return is heartbreaking.

Here, try it, Paul Timms returns, carrying a tray with two vintage teacups adorned with flowers, a tiny teapot, and a jar of jam.

I take a cup. The tea smells of mint and nettle. The jam is indeed extraordinary.

Its wonderful, I say sincerely. Ive never tasted anything like it.

He smiles sadly, looking past me.

She could do everythingsew, knit, make the garden bloom. She even made bags from leftover cloth. She always wore that little flowerembroidered bag, he nods toward his satchel. She told me not to forget it when I went to the shop.

He falls silent, and the quiet returns, heavy with his unspoken sorrow. I finish the jam, and on a sudden impulse I ask, Paul Timms, could you teach me how to make that jam? My mum cant get it right.

He looks at me as if Id said something crucial. His eyes brighten.

Ill teach you, of course. Its not hard.

And he begins to speaknot of grief, but of life. Of how he and Olly planted the vegetable patch, how she scolded him when he brought too much fabric for her crafts, how they walked together in the woods picking mushrooms. He talks, I listen, and the ghost of the grim old man finally dissolves, giving way to a solitary man who has guarded love for decades and now doesnt know where to place it.

Leaving, I glance again at the pile of unopened letters. The idea that sparked in the shop solidifies into a firm decision. I have no right not to act.

May I come back for the recipe? I ask at the door.

Come by, Milly, you must, he replies, standing in the doorway, his eyes for the first time that evening holding warmth instead of ice. Ill even tell you about zucchini jam. Its a trick.

I step onto the stairwell, the door closing softly behind me, sealing him once more in his museum of silence and memory. I descend to my flat, enter my room, and finally let out a breath.

From my pocket I pull out the comb, laying it on the desk. It still glitters with rainbowcoloured teeth, no longer just a pretty trinket but a key. A key that opened a door to anothers tragedy.

I sit, open my notebook, and begin to write. I cant pour the whole letter at oncetoo many emotions surge. I manage the first lines, the most essential:

Dear Jan, we have never met. My name is Milly, your neighbour. I beg you to find the strength to read this letter to the end

Outside, night deepens. I write, choosing words, erasing, rewriting, feeling the weight of responsibility and a strange confidence that Im doing the only possible thing.

Three weeks pass. Three weeks of silence. The letter is sent, but no reply arrivesno call, no note, no angry text. Only a hush as heavy as the quiet in Paul Timmss flat.

I visit him a few times. We share tea with jam, and he, brightening, tells me new details of his recipes. I jot them down, pretending great interest, fearing his gaze might detect my hidden motives. Each departure I feel his stare grow less wary and more grateful, and my anxiety deepens. Have I ruined everything? Did my letter only harden his daughters heart?

One afternoon, returning from university, I notice a familiar scene by our buildings entrance. A group of local aunties gathers, chatting animatedly, glancing toward the bench where Paul usually sits. Hes absent, but they continue whispering.

no wonder they called him the Grimsby. He cursed everyone, kept to himself. They say he even

I freeze, heart pounding. All that pain Id glimpsed, all the tragedy of this man they never understood, rises in me like a hot wave. I step forward without thinking.

They fall silent, eyes wide at my sudden appearance.

Youre talking about Paul Timms? I ask, my voice louder than I intended in the evening hush.

One of the bolder women, a cheeky one, snaps back, What about him? Nobody liked him. He was a nasty old fool!

Who did he argue with? I press. You or your grandchildren, when his wife was dying? Did you hear what he went through? Or are you just looking for someone to blame?

Their mouths open, then close, stunned. Confusion, embarrassment, a hint of hurt flicker across their faces. They mutter about young people thinking they know everything and drift away.

I stand alone, breathing heavily, knees trembling. Yet inside a strange calm settles. Ive said what I needed to.

A week passes uneventfully. Then Saturday arrives. Im asleep when a strange noise drifts down the corridoradults laughing, not children. I pull the curtains aside.

In the courtyard, a dark foreign car is parked by the entrance. A tall, slender woman in an elegant coat stands beside it, speaking softly.

The buildings door swings open. Paul Timms steps out, no longer in his halffur coat but in a simple vest, his face pale and bewildered. He looks at the woman, and something seems to break inside him. He freezes, unable to move.

The womanJantakes a step forward, says something I cant hear. A young lady with long blonde hair darts from the car, wraps her arms around the old man, shouting, Granddad!

He clutches her tightly, pressing her to his chest as if fearing shes a mirage. His shoulders shake. He sobsnot the quiet, bitter weeping of the stairwell, but a loud, raw wail, releasing five years of loneliness. He strokes her hair, whispering, MollyAs they embraced, the cold walls of his empty flat seemed to melt away, replaced by the warm glow of a family finally reunited.